Eros et Pulsion de Mort / Eros and the Pulsion of Death

Artists' book published in 2016 by Editions Take5 (Geneva).A scientific essay, especially written (in French) for the book,

by co-authors Pierre Magistretti and François Ansermet

illustrated by 13 original photographs by the following artists :

Anoush Abrar - Valérie Belin - Tim Davis -

Mounir Fatmi - Pierre Keller - Evangelia Kranioti -

Natacha Lesueur - David Levinthal - Annette Messager -

Vik Muniz - Sylvie Fleury

and an embossed pattern by John Armleder

Graphic design by Gina Donzé for Base Studio Geneva, and Céline Fribourg

White lacquered aluminium traycase, hosting a sculpture by Prune Nourry,

handmade in ceramic by Peter Fink workshop

A separate sewn-booklet includes a translation into English of the text, by Peter Doherty, as well as philosophical and literary quotes chosen by the artists, and a poem especially written by Carmen Campo Real

Each copy is numbered and signed by all the artists

All the photographs are signed

Dimensions: 17 x 10,7 x 2 inches - Edition of 35 copies

In psychoanalysis, "Eros" denotes the instincts of desire and life, as opposed to Thanatos, which denotes death instincts. Freud used the Greek term to mean love (Eros was the God of love), but also life instincts, in other words self-preservation and sexual impulses.

A comprehension of the roles of Eros and Thanatos involves the acceptance of a paradox, and it sheds light on the shadowy role of the unconscious. The two types of instinct, while in conflict, are intimately related and intertwined. Death instincts, though opposed to life, are inherent in Eros, in that before life there was death (in the sense of the inorganic). Eros tends towards unification and construction. Thanatos destroys. It reduces the living to nothingness. Nonetheless, paradoxically, both contribute to life, because aggressive impulses, once tamed, are indispensable to combativeness and activity. Despite their opposition, Eros and Thanatos are thus definitively creative forces, given that their oppositional duality is the wellspring of creativity, providing that Thanatos is not so dominant that it generates a morbid process. The pleasure usually associated with Eros is indeed sometimes obtained through Thanatos –perverse aggressive pleasure, for example, or the comparison of orgasm to a "petite mort" – while Thanatos is compatible with life if aggressiveness is necessary to survival in the face of danger. In general, though, if life is to be preserved, it is important that Eros should prevail over Thanatos.

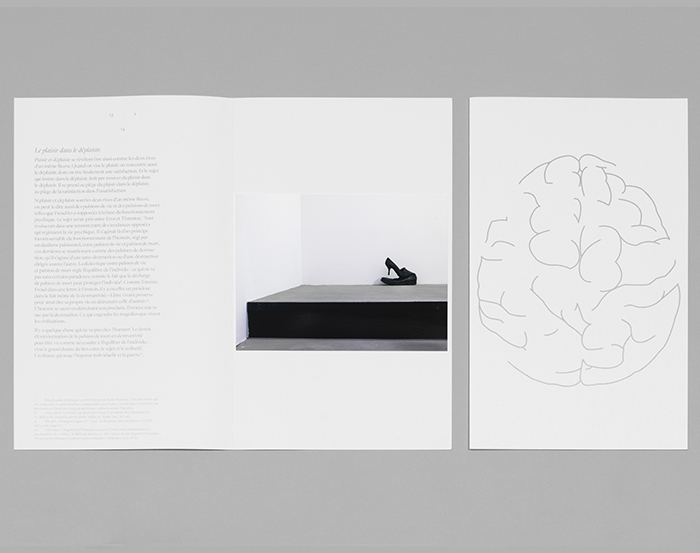

Eros and the Pulsion of Death was written jointly by the psychiatrist François Ansermet and the neurologist Prof. Pierre Magistretti, who have been working together for some years to develop a link between the neurosciences and psychoanalysis, taking into consideration the paradigm of neural plasticity. Here, they observe that between pleasant and unpleasant situations, individuals often, unwittingly, choose the latter, and that certain physiological and chemical mechanisms may bring about an addiction to displeasure. The authors explore these mechanisms, and the resulting individual and collective problems, which weigh heavily on the contemporary period. They also put forward a possible way out of this destructive instinctual spiral, through the creative process.

The artists who illustrate the text interpret the theme of impulse and desire in very different ways.

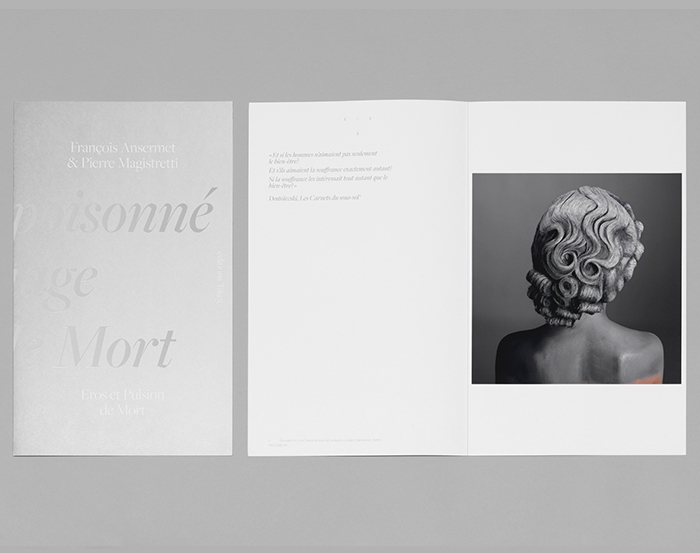

Natacha Lesueur presents a "frozen" woman, a sort of Medusa whose petrified hair personifies uncertainty, swooning or all-consuming passion. The mystery is whole and entire, and it denotes the devastating force of desire, as symbolised by light in the photograph chosen by Tim Davis, where a radiant beam infuses Icarus and Daedalus.

Mat Collishaw uses an image of fire to represent the Eros myth, with a photograph of a black raptor immolating in darkness. Evangelia Kranioti talks about the intensity of desire across the vastness of the ocean and freedom in ports, with encounters between sailors and prostitutes outside of time.

To illustrate Eros, the artist and historian David Levinthal sublimates a netsuke in a mysterious way, isolating an erotic scene that seems pervaded by the heat of desire. The image chosen by Annette Messager introduces us to different dimensions of reality and fantasy, different strata of the conscious and the unconscious mind, reason and unreason. She illustrates, with humour, the ambiguity of the romantic relationship. And there is derision in Vik Muniz' photograph, which reinterprets, with technical virtuosity and a collage method, a scandalous painting – Gustave Courbet's The Origin of the World.

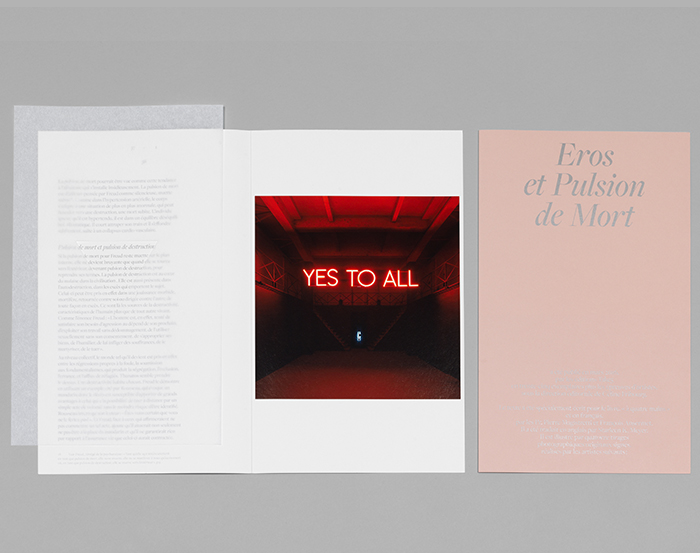

In Yes to All, Sylvie Fleury questions the hidden power of language and its associated stereotypes. This neon work displays the colour of desire, red, and the form of female genitals. But it criticises, with intense irony, the requirement that women be in a permanent state of availability. And in Eros, the Moroccan artist Mounir Fatmi photographs two erotic stelae in the archaeological site of Volubilis, to which access has recently been denied by Islamists. Here he pays tribute to the ancestral sensuality of his culture, and denounces the puritanism of the fanatics.

The last photograph, by Sylvie Fleury, disrupts the rhythm of verticality, as the emblem of Daniel Buren, in a "feminised" corolla that opens up evocative gaps.

The box that houses the book, created by Prune Nourry, suggests a pond of milk on which floats the outline of a pregnant woman, sculpted in ceramic. Nourry is interested in assisted reproduction, bioethics and the gender selection that is practised in some countries. Here, she forges a strong but subtle link between eroticism and sociology.

Valérie Belin uses a photograph of an American burlesque cabaret dancer to examine the concepts of representation and identity. Her portrait of this unconventional "doll" is reminiscent of both the surrealists' solarisations and the fascinating universe of the film noir.

FR

FR